Potholes have long been a source of heated discussion within the population basin of Greater Sudbury.

Roll back the clocks sixty years or so ago and it was “The Pothole” that was the source of hockey discussion in Falconbridge.

A neighbourhood in the local mining town that can lay claim to inventor Thomas Edison sinking the very first mine shaft in town, “The Pothole” was home to many a newsworthy hockey family, notably the Armstrong clan, apparently some of the McNamara crew, and most definitely future WHA goaltender Bob Whidden and his family.

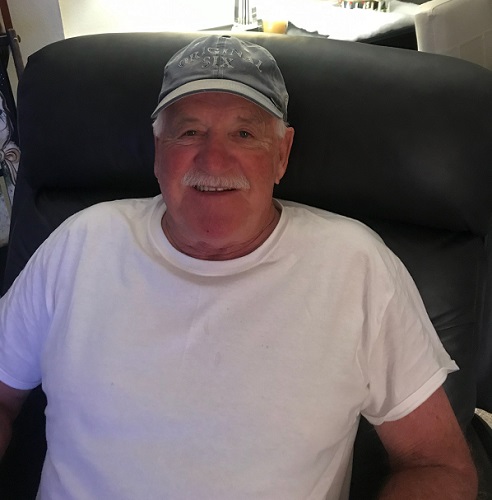

Now 76 years old and living comfortably in the Tampa Bay area since 2005 but making regular visits back home to visit his 95 year-old mother in Falconbridge, Whidden was quick to admit that goaltending was not necessarily his first choice, back in the day.

“I lived on Edison Street and a lot of the kids in that area were older than me,” said the very talented goaltender and story-teller. “When they started playing hockey, they needed a goalie and it always turns out to be the youngest one there. I started when I was five or six and they just kept me in goal and never let me out.”

Looking back, Whidden should likely thank the teammates of his youth.

At the time, in the early sixties, player dispersion typically occurred based on residency: most Falconbridge kids were steered towards the Toronto Maple Leafs; Sudbury to Detroit Red Wings; Espanola to Boston Bruins; North Bay to New York Rangers; and so on.

The era was also marked by the very gradual adoption of goalie masks for the men who stood bravely between the pipes. “The mask was introduced but it was kind of a macho thing that you didn’t want to wear the mask,” acknowledged Whidden. “When I played for the (Garson Falconbridge) Native Sons, I got cut up quite a few times.”

“I didn’t start wearing a mask until my last year of juniors with the (Toronto) Marlies.”

Central to this story was a highly recognizable hockey name, one of several that Whidden can intertwine delightfully as he regales a room with memories of his time on the ice. During the 1966-1967 season, the future pro was helping to backstop the above-noted Marlies to a Memorial Cup – coincidentally during the same year that another GTA team would hoist the hardware.

“I was out practicing with the Leafs in the morning,” Whidden recalled. “(Johnny) Bower and (Terry) Sawchuk were playing and (Punch) Imlach would give one of them the day off after a night game. I would practice with them in the morning and then we had our Marlies practice at night.”

“I was out with Sawchuk and he says to me, “Bob, you’re going to get killed out there”.”

Already donning the mask, Sawchuk made arrangements with Detroit Red Wings trainer Lefty Wilson to equip Whidden with some form of protection – and the northern lad never looked back.

Following a very good showing in his first NHL training camp in Toronto, Whidden bounced around the minors for a few years, set back with some injuries woes to his back. Still, a pair of solid seasons with the Charlotte Checkers of the EHL had kept him at least in the conversation as a new league emerged.

“We came back to Sudbury,” said Whidden, reminiscing on the summer of 1972 with his wife, Irma. “We had a place on Lake Wahnapitae that Danny McCourt later rented and I was working for Tepper Caverson with Molson’s Breweries.”

A phone call from World Hockey Association (WHA) officials would see Whidden and a local lawyer make the trek to Toronto, part of a gathering at the Royal York that would introduce the pair to “Wild Bill” Hunter, founder of the WHL and co-owner of the new league – and a key member of the group that eventually created the Edmonton Oilers.

“They doubled what I made in Baltimore the year before and sent me to Cleveland to back-up Gerry Cheevers,” said Whidden. “It was a fabulous time of my life.”

Those of a certain age will recall the exodus of Bobby Hull and Gordie Howe and others to the new loop, a fledgling enterprise intent on using any opportunity available to promote their name talent. “Gordie was in Cleveland for an autograph signing session on Thanksgiving weekend – and I was his chaperone,” said Whidden.

“He had an early flight out and I lived five minutes from the airport, so I invited him to stay at our place for the night. He was up until about two in the morning, talking to my boys and eating my wife’s turkey sandwiches.”

His playing days coming to an end in 1976, a second back injury essentially making the decision for him, Whidden and family would remain in Cleveland until 2005, at which time he and Irma would make their way to Florida and his now long-time home off the Gulf of Mexico.

“I’ve been blessed,” he stated, without the slightest hint of regret.

Involved with the ownership group that would bring the Muskegon Lumberjacks of the IHL to Cleveland and later as head coach for 21 years of the storied St Edward High School hockey program that produced a small handful of NHLers and countless NCAA recruits, Whidden was more than happy to keep his hand in a game that he love.

“I’m still a big fan of the game; I watch it a lot,” he said. “I’ve seen it evolve from fifties and sixties, through the seventies and eighties. Every generation, it’s evolved. These guys now can shoot the puck through an eye-hole; it’s just amazing.”

“I would like to see a little more body contact. I would like to see the guys learn how to use the boards a little more, to be able to take a guy into the boards cleanly.”

“But overall, I like the game. It’s superior to anything that we ever had.”